Journey Toward Hip Replacement – Lorna Kleidman

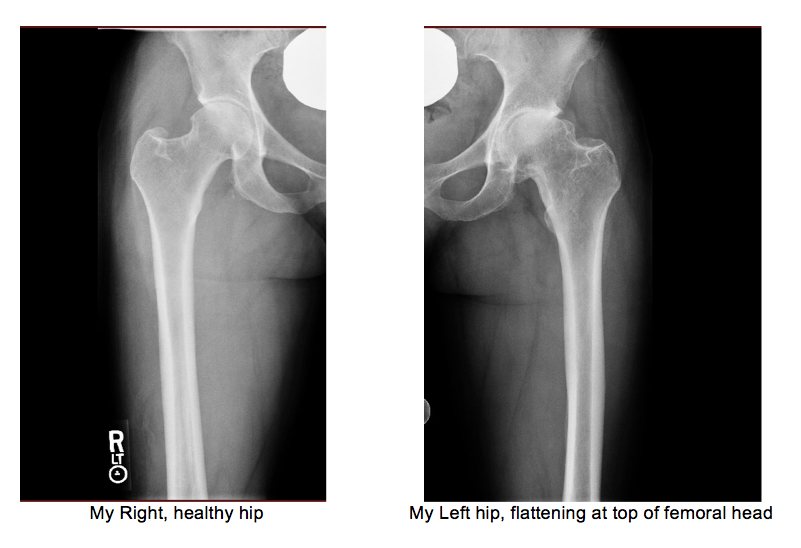

In June of 2016 I had a full left hip replacement at the age of 50. Many people naturally associate joint replacement surgery with advanced age, but it’s not uncommon to hear stories of younger individuals in their 30s also needing the procedure for various reasons. Mine was due to genetics dictating the shape of my hips and the placement of my femur heads being set fairly high with little room in the sockets, compared to a typical female hip. Even as a teen, my left hip was more limited than the right. While I wasn’t experiencing any pain, my mobility gradually became less and less each year, leaving me unable to freely and fully participate in activities that I love. My condition was Osteoarthritis.

Osteoarthritis or “OA”: A joint disease mainly affecting the cartilage – slippery tissue that covers the ends of bones in a joint. OA is the most common chronic condition of the joints, affecting approximately 27 million Americans.

There are two things that need to be made clear right away:

1- Lifting weights of any kind did not create the need for surgery – it actually allowed me to compensate for my OA and was extremely beneficial in shortening my recovery time.

2- This was not due to an injury. Over the past 16 years of working out at a high level, with 8 of them involving specific training to perform in competitive Kettlebell Sport, I can say that I’ve never been injured in any way. No muscle tears or sprains, no back, neck, shoulder or knee issues. I never missed my routine workouts or training over the years other than due to a rare cold, much appreciated vacations, or simply treating myself to an additional few days of recovery time.

As I mentioned above, the extraordinary part is that I never had pain in all the years prior to surgery. Even in the last months when the articular cartilage within the joint capsule was gone and the femur head was bone-to-bone with the acetabulum (socket of hip), there was no pain.

What I did have was extremely limited motion, with an occasional slight achiness after a long jog or very heavy lifting session, but nothing unusual. Nothing like one would assume given the eventual deterioration of the joint complex. The reason for the surgery had nothing to do with being an athlete, lifting kettlebells or other weights. The truth is that at some point I’d have to go through this procedure, no matter how active I was. Supple hips are something I’ve never had but I was able to function at a very high level without pain because my hip and leg muscles were strong. Strong muscles support bones. Make no mistake – I was without pain because I lifted weights.

I was without pain because I lifted weights.

So if there’s no pain, why have surgery? The answer is that there came a point when the lack of motion progressed to being more than just an inconvenience. It was more than simply being uncomfortable when sitting in a theater, on an airplane or at dinner. More than having to reduce my squat, deadlift and lunge to ridiculously shallow depths. More than having to give up yoga and being unable to demonstrate movements for clients.

In the last year putting a shoe on my left foot became challenging and squatting with weight was increasingly awkward – I was hardly able to tap my butt to a bench with 2 pads on it! Even then my hip was torquing to accommodate flexion. As strong as I was, I lacked mobility ten-fold. Lastly, I dreaded bending over to pick up anything and even dreaded having to tie my sneakers or strap on my high heels The simple act of bending to pick up an item became a misery. It was clearly time.

Video from 2011 – Began to reduce range but still relatively healthy joint at this point

Physical Structure & Ability

As a teen, jazz and ballet classes were my passion. Loving the technical side of dance I worked to get my non-supple hips to turn out as much as possible, after all, it’s how proper ballet is done. While other classmates’ pre-session rituals included hanging out in splits, I could only hope to achieve such extension once the class was over and I was thoroughly warm. Even then it would have to be a ‘good day’. Ballet and floor barre, along with kickboxing to a heavy bag which I took up years later, are probably the most destructive activities for joints with limited ranges of motion, but of course they felt fine at the time.

One day, at the age of 38, I felt a random clicking and discomfort in the front of the left hip. This sensation continued sporadically when I walked and jogged. It wasn’t a sharp pain, but a restriction I couldn’t identify. Assuming it was a muscular issue, I tried to stretch in various lunges, with no relief. Within weeks all motions began to worsen: internal rotation, abduction, extension and in particular, flexion, was only possible with accompanying abduction (bringing leg to the left of midline) of the femur. No longer was a seated flexed-knee spinal twist available, nor was crossing my left leg over the right. These would not return until after surgery.

Doing a straight-legged seated floor stretch used to be chest on thighs, yet now it was a bent-knee version while leaning my trunk to an upright block so as to relieve the compression in the left anterior compartment. Forward lunging from Plank position was impossible without my hand on a block, then two, to make room to get the leg through due to reduced flexion.

Internal rotation was impossible from the start and flexion was only possible with accompanying abduction of the femur.

I could still jog and continued to do so until surgery, but over the years leg extension became shortened. In order to move, my body compensated by slightly rotating the left hip open, just enough to give the leg room to extend. None of this was conscious of course; my alignment specialist, who’s kept me structurally sound for many years, brought it to my attention, along with a compensatory limp that was noticeable to others as far back as nine years ago.

A year after the initial sensation in the anterior hip, an MRI indicated a ‘frayed labrum’. This is the cartilage that acts as a shock absorber and maintains fluid within the joint. Figuring it would gradually heal, my trainer and I modified the ranges for the major lifts, as necessary. The discomfort did abate, but the joint was already deteriorating.

First Visits to HSS, 2014

After x-rays and a consultation with Dr. Kelly, I was told that the only remedy would be a full replacement. This was rather shocking, to say the least. As I had no knowledge regarding this procedure, I immediately starting doing research. I heard about Dr. Philippone at the Steadman Clinic in Vail, who came highly recommended by a friend. Not surprisingly, his reply was that my hip was too far gone for the type of procedure he performs. Upon urgently requesting a NYC referral, I was told to see Dr. Paul Pellicci at Hospital for Special Surgery (HSS). An appointment was made for 5 weeks later. Just an indication of timing and how many people require this type of procedure.

“Never underestimate the ability of a doctor to make you worse,” was the first thing Dr. P said after he listened to my complaints of inability to do yoga or deep squats. I had more limitations than these, but in the moment I couldn’t seem to recall them. The x-rays showed bone spurs and thinning of the joint cartilage, yet without hesitation he stated that my grievances were an inconvenience and therefore surgery was premature. “You shouldn’t have surgery unless and until you’re in pain,” was the message. I had heard this before from everyone who knew anyone who’d had the procedure. Yet as I left the office, I knew pain wouldn’t be part of my experience for years, if ever. It seemed as if my body would simply continue to compensate before pain would set in. Would I have to wait 5 or 6 years to get this done? On the one hand I could live with the situation, though it wasn’t optimal. On the other hand I’d heard of doctors that would be happy to perform the surgery and I’d be back to normal….maybe. I put the issue to the side for the time being.

“Never underestimate the ability of a doc to make you worse”

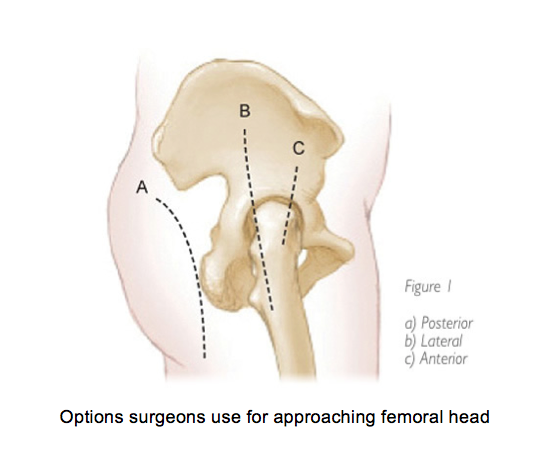

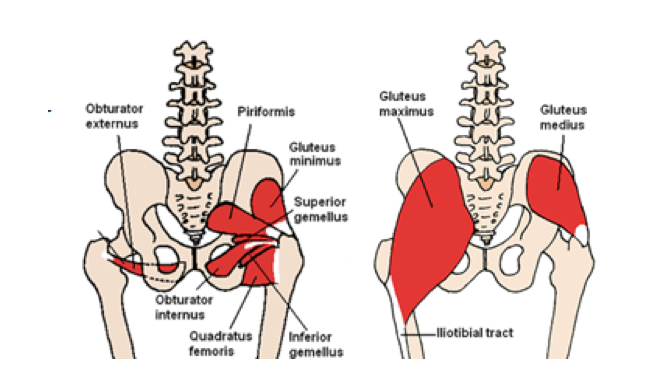

Dr. P. was firm in his conviction that a posterior approach was the optimal way to perform hip surgery, and though the anterior approach is the ‘new norm’, it’s not proven to be superior. He stated a 60% risk of sensory nerve damage with ensuing numbness in quadriceps muscles, along with 15% risk of acquiring a permanent limp. SAY NO MORE!

The posterior approach he performs involves very little tissue disturbance: The conjoined tendon of the two gemelli and the piriformis tendon are separated from their attachments on the femur (not by cutting the muscles but by removing their tendon). They are then replaced with cement upon closing. The gluteus maximus is also separated, but not cut, in such a way as to gain access to the femur head and acetabulum.

The two years that followed were physically successful ones, since the competition Snatch movement that I train for requires a rather short range of motion from the lower body. I also ran my first and probably only half marathon, which was a terrific experience. Eventually there were difficulties in sitting, travelling and putting on shoes, as mentioned above.

Second Visit, Winter 2016

On the second visit Dr. P expressed his amazement that I was so functional giventhat new images showed bone-on-bone with a flattening of the femoral head. “So we can do the surgery?” I was ready to beg if necessary. “Yes.” YES!!! Materials would be ceramic and plastic, with the ability to jog again when I’m up to it. The only precautions while healing were avoiding hip flexion to 90*, adduction (crossing midline of body) and internal rotation. Physical therapy was not necessary. The only prescription was walking, simple leg movements, ankle circles and platar/dorsi flexion. Once I felt ready, I could begin body weight movements. CAN’T WAIT!

June 21st, 2016 – Surgery

Wasn’t nervous until moments prior to being wheeled into OR. The worst part was being outfitted with 4 tubes: IV, antibiotic, epidural tube (placed after I was asleep) and later a catheter. Fun times! Woke without pain, realizing I had no ability to move my legs or toes. The femur was wrapped with large ACE bandages for compression and lower legs had air pump wraps around them to prevent swelling.

Epidural wore off about four hours after the procedure. One of the nurses, who was just about to go home for the night, came down to the recovery, helped me sit up, shift legs, and walk a bit with a walker. Dr. P came by, reassuringly stating that my hip had in fact been “terrible.” Once transferred to the semi-private room, I ate a bit and watched TV. Six more hours passed, not able to sleep. Pressed the self-administered oxycodone once for an extra dose, but still no sleep. Finally the sun rose and had vitals taken along with another walk. The staff was beyond fabulous!

Day 2

Walking –

Mid-morning I walked with the cane, a bit awkward but not too uncomfortable. Third walk of the day was to learn how to use stairs with the cane. Since I hadn’t slept all night I was eager to get home and insisted that it would be best for me to get into my own bed and there I’d be able to sleep. Finally, the staff relented and my staples were removed, but sleep would not come for a long time.

Day 3

As the nurses predicted, today was the most pain, along with oxycodone causing horrible headaches in the morning hours. Stayed home and walked the hallway morning, afternoon, and evening.

Day 4

Walking in Park –

Sleeping and sitting in a chair were the two most difficult aspects of recovery. Tossing about is part of my pre-sleep ritual, but with pillows between the knees, a very heavy leg and tenderness with movement, decent sleep wasn’t possible but for 30 minutes here or there. Sitting to eat at a table versus on the sofa was a challenge since the leg could not yet lift to flex, the result was slouching in the chair.

Day 5

Off oxycodone since headaches are worse than minor hip discomfort. Relied now on the suggested dosage of Tylenol 3 times per day plus aspirin and something for stomach protection.

Never a fan of pills, but took Ambien for a few weeks. Walking & feeling better in general but quadricep muscles are extremely tender to touch and difficult to stretch. My theory is the muscles endured tears where they attach on the length of the femur when the stem is hammered into the bone. Sorry if it’s TMI. Interestingly, no bruising occurred at the incision site but draining did show up on the entire left inner thigh and calf regions.

Day 6

Walk in Park again and go to gym: Lower body range of motion (ROM), assisted squats, upper body weights. Feels great!

Day 7

Trying walk without cane –

Gym: General ROM, bike 20 min, machine row and posterior fly, pushups, calf raise, gentle hip flexion/mobility.

At times while sitting (slouching) there would come waves of nervous system over-stimulation with a spontaneous feeling of nausea, albeit subtle. Standing and walking usually helped, but standing from a seat also required a few moments in order to accommodate body weight on the new joint before ambulating. As the weeks passed it became gradually easier to get up and walk without hesitation.

Day 13

Walking stairs unassisted-

Day 14

1st full day walking unassisted –

Walk fountain stairs in Park 20x

Week 3

Gentle workouts including bells: 12kg Swing and Snatch. Stairs in building 7 flights 5x

Week 4

Resume (gently) strength and conditioning with trainer and simple, slow yoga at home

Week 6

Walking-

Week 7

Slow jog intervals outside: 30 sec/30 sec walk. Later in week 1 min/30s walk.

See Dr P for check up and new images. I’m told there are no restrictions at this point, just avoid aggressive internal rotation of femur.

Video before and after –

Special thanks to my husband for taking great care of me!

If you or someone you know could benefit from this article, please share.

Feel free to contact me – Lorna@LornaFit.com

Best, Lorna Kleidman

www.SPRYoga.com